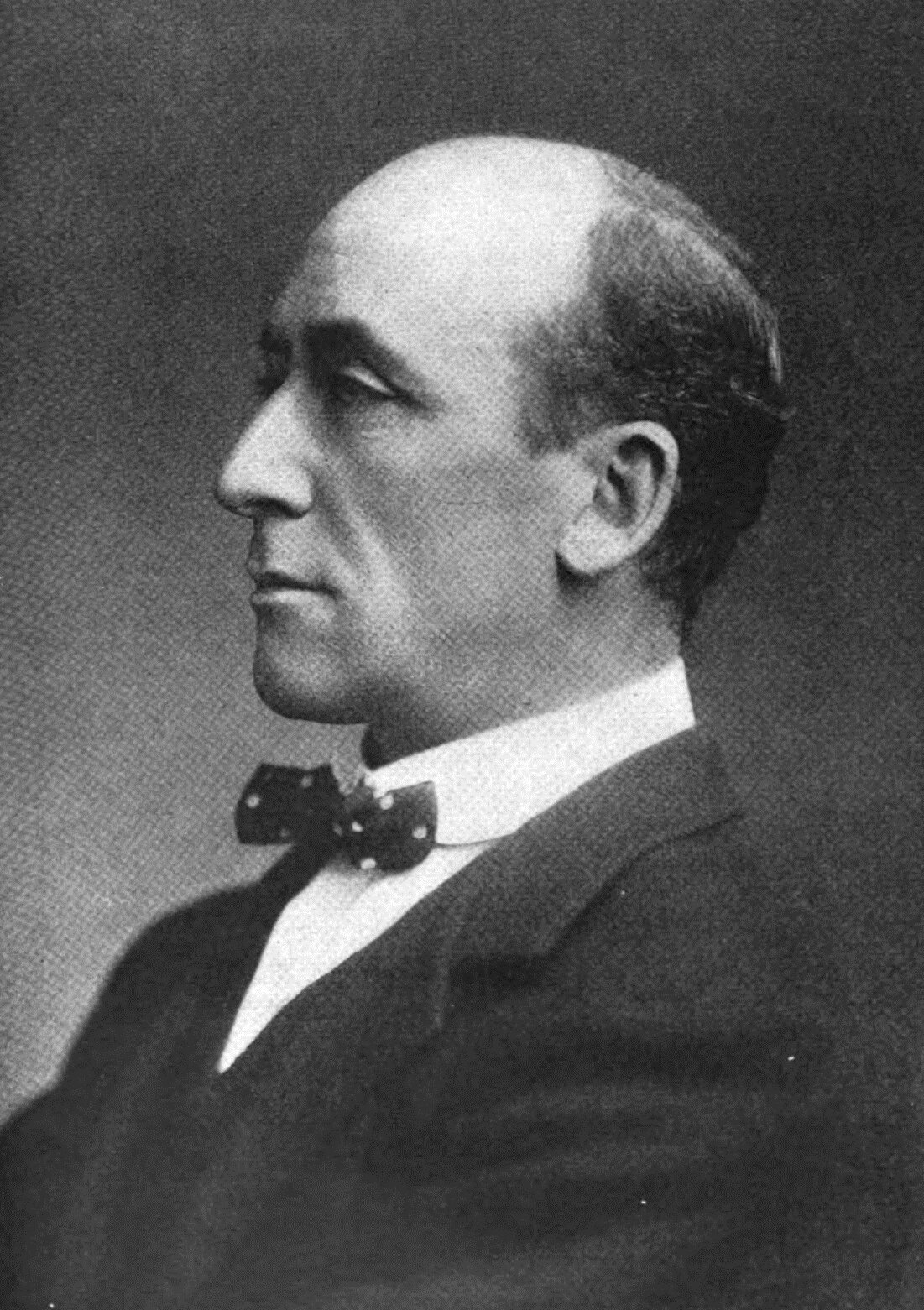

Algernon Blackwood: Life & Works

Algernon Blackwood (1869-1951)

Algernon Blackwood was born in South-East London in 1869, and grew up in a religious household. His parents were Calvinists, which entailed an austere, narrow, and oppressive childhood. As a teenager he was even sent to an isolated Moravian Brotherhood school in the German countryside, and in a later biography he described his life there at that time - the harsh pietism which prompted his imagination to flee into the German Black Forest, where he could discern the Germanic animistic spirits at play. Animism is the religious belief that all objects, places, and creatures, are infused with some kind of spiritual essence, almost as if there is a living memory in all plants, rocks, rivers, and in the soil itself. You could even understand ‘The Collective Unconscious’, which I spoke about last week, as Carl Jung’s attempt to capture animism in psychological terms: this collective memory which bubbles out from unknown depths.

On a slight tangent, in 1936, some 40-odd years after Blackwood’s imagination wandered amongst the trees of the Black Forest, and a couple of years prior to the outbreak of World War II, Carl Jung actually wrote an essay on ‘The Collective Unconscious’ specifically in relation to the Black Forest. In it he argued that old Germanic folklore traditions, dormant within the depths of the Black Forest, were beginning to resurface and re-assert themselves, much like dormant volcanoes becoming once again active. Namely, the German God of storm and frenzy, Wotan. A return made possible given that Christianity had receded in its dominance, leaving a vacuum to be filled. The spirit of Wotan was most apparent in the Youth movements of Germany, and in Germany’s most dominant political party at the time – the National Socialism Party, AKA the Nazis. I wonder then, if teenage Algernon Blackwood also intuited that same animistic spirit, dormant and biding its time, in the wake of the doom it would inevitably loose upon the face of Europe.

Anyway, in the light of all this strict pietism and the restrained lifestyle he was expected to lead, when Blackwood finally did leave home, aged 21, he had never consumed alcohol, he had never had a cigarette, he had never seen a movie, or held a pack of cards, nor had he even read material outside of what was deemed appropriate for an upright Christian to read. And so, finally free of his parent’s rules, he made up for it, especially in terms of what he read. He was determined to explore religious ideas in more general terms, exploring, in particular, Eastern philosophies and religions, Hinduism and Buddhism, as well as more esoteric subjects, such as hypnosis and clairvoyance. During this early adulthood period, he had an eclectic set of jobs. He moved to Canada for a time, where he worked on a dairy farm. He managed a hotel in Canada for a period; he worked in New York city for a time, as a bartender, a private secretary, a violin teacher, and as a journalist for ‘The New York Times’. All the while making the most of America’s rugged landscape, being in Nature, hunting elk, and finding others’ indifferent attitudes towards Nature, and her beauty, intolerable. And then finally, in his late thirties, he moved back to England, where he began to write his stories of the supernatural, which he became known for.

The key to this horror then, is its unknowability, its strange otherworldliness (not wholly dissimilar to that disembodied hand), because it’s the inexplicable nature of that scene at Belshazzar’s Feast, that handwriting on the wall which makes King Belshazzar so fearful, that in turn makes this episode so compelling. For it certainly is mysterious, and bizarre. And as the author intended, so we also are invited not simply to appreciate the macabre, but also to revel in the fear of Belshazzar, for Belshazzar is an enemy, a foreign king. And so, it’s probably fair to say that the seeds of horror fiction are first planted here in the Bible - that same Bible that Blackwood was compelled to study exhaustively, and no doubt he took some moderate satisfaction in reading and considering the stranger and more inexplicable passages the Bible has to offer. But as I said, it was Nature which was the greatest inspiration for Blackwood. He felt that it was only within Nature that one could be truly at liberty. Blackwood’s Nature was sentient, and alive with unseen powers, a belief which was fuelled by his teenage experience in the Black forest, his interest in Eastern mysticism, and while in New York his involvement with the Theosophical Society. He was ever mindful of the exceptional which lay just beneath the ordinary. The "gap between spiritual brilliance and dull appearance".

But as previously mentioned, it was not until 1899 when he returned to England, that the writing portion of his life began. We can compare him to MR James, for they both began writing ghost stories around the same time, right at the turn of the century. MR James and Algernon Blackwood were both lifelong bachelors, although Blackwood was much more the recluse. But whereas James wrote his stories in nice Cambridge rooms, being the academic that he was, Blackwood wrote in boarding houses, a last ditch attempt to make some money when there was nothing left to pawn. But with moderate early success, he was able to return to what he loved: Nature. He travelled throughout Europe, hiking and climbing in Italy, France, Spain, Austria, and on a couple of summers canoeing along the Danube river, through Hungary. And it was this experience, canoeing through and exploring Hungary, which inspired his most famous piece of work, the one I read a little from, “The Willows.” The short story in its entirety is not very long. I read it all in less than a couple of hours, and it’s now out of copyright, so you can easily find it online. In summary, the story is told from the perspective of an unnamed narrator and his companion, who is referred to as ‘The Swede’. The fact that Blackwood was not much of a people person is reflected in his stories; character is never very important for him. And the unnamed narrator is clearly himself. Many of Blackwood’s stories are as veiled self-portrayals, with the bizarre and unworldly elements acting almost like philosophical questions that he would pose himself – ‘what if’ questions, that lead him into his speculative uncanny worlds.

So this pair then, come to “a region of singular loneliness and desolation,” where willow-covered islands grow and shrink overnight amid the rapids. This is the eerie setting. The adventurers pitch their camp on one such island, as no doubt Blackwood did also when he travelled these parts. The sun goes down, and the wind increases, and terror strikes… monstrous bronze-colored figures dancing and rising up to the sky. The narrator tries to convince himself that he’s dreaming, but to no avail. In the morning they both wake to discover their canoe has been sabotaged, sabotaged on this remote, isolated island. They attempt to repair the canoe. As they talk, the Swede explains that he’s been conscious of such “other” regions his whole life, full of “immense and terrible personalities.. compared to which earthly affairs… are all as dust in the balance.” Their only chance of survival is to keep perfectly still, and above all to keep their minds quiet so that “they” can’t feel them. They continue to be tormented. There is a torrent of humming that surrounds them, and ultimately the story concludes with them finding a body in the willow branches, that upon touching causes the presence, the hum, to rise into the sky and abate. The spirits have accepted this nameless peasant as an acceptable sacrifice.

This all invokes then, our atomistic, and dust-like nature, the absurdity of the human condition. We who wrap ourselves up so intensely in our own affairs, which against this vast and mysterious backdrop, is an absurd puppet show, ultimately meaningless. So, I think that’s the ultimate takeaway. Unlike Lovecraft, whose stories are nihilistic and lead us to an ultimately hopeless and pessimistic place, Blackwood takes us in the opposite direction. In the face of the inexplicable, he tends towards hope and optimism. Not so much for those in the story, but for us. An optimism that we might seize on this broader frame upon things, that doesn’t shut the world down into materialistic certainties, but opens the world up to all its creative possibilities. Let us all take the wider view, and create space for the inexplicable.

Amen.