And Then We Became Gods

Yuval Harari

Last week, I mentioned in passing the author Yuval Harari. Yuval Noah Harari is a historian and professor who works in the Department of History at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He is an Israeli, an Oxford graduate, and has published several books, but by far his most notable are his two most recent: ‘Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind’, which was published in 2014, and ‘Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow’, which was published last year. I picked up on a couple of the themes in his first book ‘Sapiens’ in last week’s address. In Sapiens, Yuval Harari attempts to explain what it is about us, about human beings, which has allowed us to achieve so much. He, very convincingly I think, puts it down to humanity’s ability to weave elaborate fictions, or create elaborate mythologies, which harness large scale cooperation. When we think of mythologies, we naturally think of religions, like Christianity or Islam, but it goes much further than that. These fictions include economic systems like capitalism, or corporations, or the fact that we, without even thinking about it, imbue money with value. Or indeed geopolitical entities like the European Union, or the United Kingdom. None of these things are really real, but they are made real because it is agreed collectively that they are. In turn these fictions arrest our human agency, they frame the way we see the world, and therefore fundamentally guide the way we live and operate in the world.

Behold Christendom!

Take, for example, our relationship to Christianity. When we think about the various tenets of the Christian faith, we are able to compartmentalise. We take a step back, we gain some objectivity, and we think to ourselves what bits of the Christian narrative seem credible to us, and what bits of the Christian narrative don’t - Jesus being an historical person? Yeah, we can go along with that. Jesus walking on water, or flying, or the miracles? Well it doesn’t seem very likely, so we look for a more allegorical way of understanding those parts. And so on… The fact that we are able to do this demonstrates how weak the Christian mythos is. We don’t accept it implicitly, we hold our own rationality or intuitive sense over and above the Christian narrative, which is pretty strange if you think about it. How arrogant it is for us to believe our half-baked opinions carry more weight than the Christian narrative. But we do.

But of course, it’s not just us. All Christians today are doing this, from those on the edge, to hard core bible-thumping Christians. They’re all weighing the texts, emphasizing certain parts, and explaining other parts away. Conservative Christians however have the added advantage that they can pray about it, and therefore convince themselves that this process is being guided not by their own egos, but by God. Compare that then, our contemporary relationship to Christianity, with a Medieval person’s relationship to Christianity. In medieval times, people didn’t choose to become Christians. It was the dominant narrative. People were already in the fish tank, and as such were not capable of gaining objective distance, and weighing those beliefs against some other criteria. It’s not even right to say that everyone accepted the Christian mythos, because that suggests a choice is taking place. In Europe, or Christendom, should I say, the Christian narrative was simply ‘the’ narrative. As I said last week, we can leave this Meeting House and before we say anything to a stranger we can assume they buy into the ten-pound note fiction. In the same way, in Medieval times we could have assumed people bought into the Christian fiction. In those times, in Christendom, it would have been impossible to imagine a time beyond the dominance of the Christian mythos. Post-Christendom would have been utterly inconceivable. One could have sooner imagined an apocalyptic, fire and brimstone ending of the world, before one could have imagined the end of Christendom. Today, the most dominant fiction, the most dominant narrative, is that of Capitalism, and as the Mark Fisher quote goes… ‘It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of Capitalism.’

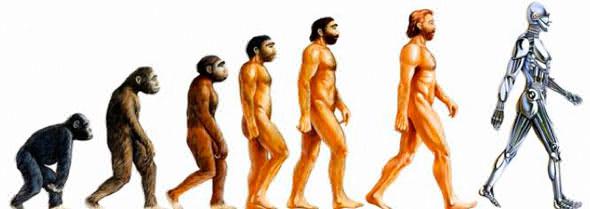

Evolution of man

Anyway, that was all preamble. What I really wanted to talk about today is Yuval Noah Harari’s second book, ‘Homo Deus: A brief history of Tomorrow’. His first book has gotten us up to now. ‘Homo Deus’ explores the different possibilities unfolding on our horizon - what’s in store for us over the next few decades. And of course, the story of tomorrow is the story of computers: the rise of artificial intelligence, the real potential that ‘artificial intelligence’ will become the dominant life-form on earth, and what that might mean for us, for Homo Sapiens. For the last 4 billion years life has solely existed within the biological arena, evolution through natural selection. Whether you’re a microorganism, or a crow, or a fox, or a human being, we are all made up of organic matter. But now we are on the verge of allowing life to break out of the organic realm into the inorganic. This possibility is not simply the most important revolution within our human history, but the most important since life began. The implications of this are of course incredibly wide-ranging, for society, for politics, for human beings. Yuval Harari explores many of these avenues, but he focuses on what it might mean in more concrete terms for us over the next few decades, for us and our jobs, for us and our relationship to the world’s most dominant narrative - Capitalism.

More and more experts are talking about how in the next few decades, artificial intelligence is going to push human beings out of the job market, resulting in a whole new class of people: the useless class - a huge amount of people that in economic terms will have no value at all.

This is standard market forces at work. The employer chooses the best possible person at the lowest possible cost, As soon as the best possible person is a computer, the employer will pick the computer, because it is much cheaper to plug in a computer than it is to hire an employee. Computers don’t require a pension or anything. The people left over are not simply unemployed, they are unemployable. Take doctors as an example. If I’m sick, I go to the NHS to see my doctor. I go, ‘Aaaaa’, the doctor looks in my mouth, she may use her stethoscope and listen to my chest, she will ask a few questions, and in less than ten minutes she will make an assessment of my medical condition, based on these few data points, and maybe a little knowledge of my medical history. But she is a human being, she may not be operating at her peak performance, she may be tired or stressed. She probably is. She is human being, so even if she is the best doctor in the world, she cannot possibly know everything which could be wrong with me. Artificial intelligence is being developed to do the work of doctors. Artificial intelligence will not use a few data points, but every data point. They will monitor our health 27/7 from our phones, they will access every piece of data from our history, and they will know all possible diseases I could have. They will not be constrained by time factors, or have off days. AI (Artificial Intelligent) doctors would not have been trained a few decades prior, but be up to date on all medical development to the second. The traditionalist inside you may still think they would rather see a human being, but what if I could show you the data that proved you were more likely to die if you saw a human doctor? Who would take that gamble? I certainly wouldn’t. And in this way human doctors will become useless to society, their economic value will be reduced to nothing, they will join the useless class. Not just unemployed but unemployable.

Robots taking our jobs!

Yuval Harari is not alone in postulating that in the next 10-20-30 years, employment in the West will fall by more than 80%. Lawyers, teachers, across the board. Humans have essentially two things going for us - our physical ability, and our mental ability. The industrial revolution of the 19th Century was about machines doing the physical aspects of our work better than us. The Luddites tried to resist, but it was futile. Why employ a room of weavers, when a textile machine can produce more at lower cost? Why employ hundreds of people to bring in the crop on your farm, when it only takes one combine harvester? Machines pushed most people out of the physical labour market, and into the labour market of the mind, into the realm of lawyers, programmers, publicity, design, insurance sales, care professions, and so on… The Artificial Intelligence revolution will push humans out of the labour market of the mind as well. But that will leave us with nowhere to go. As the useless class grows over the next few decades, what will happen to them, what will happen to us? We can try to guess and imagine, but we don’t really know. One possibility is that the useless class becomes politically dominant, and we are able to restructure society to benefit the useless class, and make sure society at large provides for the useless class. But, historically, there has been a strong correlation between one’s economic value within society and one’s political power. So the more dystopian possibility is that the vast majority of people find themselves unemployed and disenfranchised. We’re all left out, and politically disempowered to effect change.

It seems to me that part of our task over the next few decades is to make sure that does not happen. We must strive to maintain, or where possible increase, our own political agency, because if our political value is defined by our economic value, then our political value is in danger of being snatched from us. So, this brings me back to the dominant narrative of our age: Capitalism. This fiction has been an incredibly powerful one; it has enabled us to utilise human cooperation like never before, it has empowered individuals, and lifted millions of people out of poverty. Today in the world you are more likely to die of old age than an infectious disease. Today in the world you are more likely to take your own life, than be killed in war or by terrorists. Today in the world you are more likely to die from eating too much, than of starvation. If this is what success looks like, Capitalism can take a lot of credit. However, despite all this, despite the capitalist success story, it seems that now this narrative, this fiction, is in danger of checkmating us. Because this fiction is about to reevaluate us…